Women Readers: Considering the Anti-Feminist History of the Comic Book Industry and Foundational Graphic Novel Works

![]() [CONTENT WARNING: Contains discussion and/or pictorial depictions of sexual assault; violence against women; genocide; suicide.]

[CONTENT WARNING: Contains discussion and/or pictorial depictions of sexual assault; violence against women; genocide; suicide.]

"Antifeminism continues to be a characteristic present in much modern graphic literature, yet the industry remains a site of contention with regard to the issue of feminism." —Thomas Donaldson1

Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen, Maus, and The Sandman, are crucial American comics works that form part of the canon of graphic novels of the 20th century as revolutionary and enduring novels for adult readers that helped to define graphic novels, legitimize the format as literary, increase comics readership and recognition, and promote a widespread public understanding that stories could come in comic form. But many such canon graphic novel works of the mid-80s to the end of the century demonstrate the industry's long-standing focus on catering to male readers.2

The comic book industry has arguably been "antifeminist in its orientation" since the beginning, with the particular focus on "adventure-oriented genres" that expressed that "women's limited role in the public sphere was for the best."3 However, women were once the majority of comics readers in the US, particularly during the 40s when romance comics for grown-ups (compared to the romance in Archie comics, for example) were immensely popular.4 But the "moral panic about comics" and the introduction of the Comics Code in 1954 decimated the genre, being so altered by the code that women readers moved on to romance novels, which were less censored.5 This significant drop in female readership led publishers to increasingly cater to the young men (in their teens and early twenties), and by the 70s, there was little comics content that was geared towards women—giving them the impression that "comics were not for them."6 By the 80s, the industry shifted to direct distribution (vs. independent distribution), which moved the comics scene to small specialty comic book stores—frequented and staffed by young men.7 With stores having little room to stock back issues and dedicated readers needing to keep on top of comics news and have ties to the comics fandom to know what titles to order/reserve and when, the direct-distribution system alienated women readers further.8

In the early 70s, the comics industry "confronted" second-wave feminism by "portray[ing] women's liberation as a spurious, perhaps dangerous movement."9 But in response to feminist criticism, the industry began "developing female superheroes who presented a more powerful vision of femininity" in the mid- to late 70s.10 However, despite these characters capturing some feminist aspects, the creators of such characters, in adhering them to the "superhero convention," would always make the world return to "'normal' when a villain was defeated—with these heroines using violence as the "primary mode of conflict resolution" and preserv[ing] the very system that they ostensibly s[ought] to reform as feminists.11 The 80s saw the industry backpedalling away from feminism and female leading characters in a parallel to the "'backlash' against second-wave feminism in popular culture and politics," reverting these characters to secondary roles.12 Furthermore, misogyny prevailed in the industry, with mainstream creators having "initiated a pattern of destructive victimization and/or humiliation of female characters"—from physical abuse, superpower deprivation, loss of identity, rape, and death.13 And when no longer bound by the restrictions of the Comic Code, comics increasingly featured women characters as "little more than sex objects."14 With its lengthy history of misogyny, the mainstream comics industry, particularly the superhero genre, is "defined by this tradition of antifeminism."15 Although female readership has exploded since the 90s, women readers still "tend to gravitate toward specific types of content" associated with gender and "female-targeted storytelling."16 Paying particular attention to this history of misogyny and exclusion of women readers an important and worthwhile exercise in considering key graphic novel works of the canon that form the foundation of our understanding of graphic novels—especially considering how unwelcoming the world of comics can still be for women in the industry and women readers.

Comics fans dressed up in costume at San Diego Comic-Con in 1974.17

Batman: The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller

"…probably the finest piece of comic art ever to be published in a popular edition…" —Stephen King18

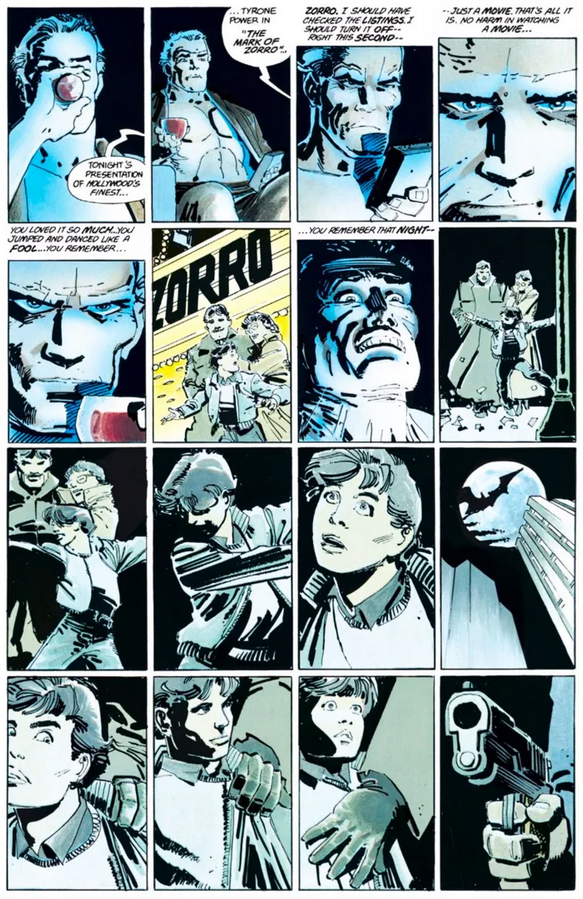

Bruce Wayne is overcome by the memory of the night his parents were murdered.19

The deep and cynical Batman of The Dark Knight Returns presents the caped crusader's crime-fighting as a "psychological compell[ing]," with a fifty-year-old Batman recruiting a new Robin (following the death of the original) and saving Gotham City once again, but "it's a bleak world he saves."20 Miller questions the role and justice of vigilantes in a democratic system, even showing Superman as a naive government pawn.21 Being the writer and artist, Miller experimented with page layouts to "purposefully disorient the reader," in addition to setting a dark mood with the colour tones.22 The collected volume in 1987 was printed as a "'prestige' edition" on expensive paper—a packaging meant for adult readers.23

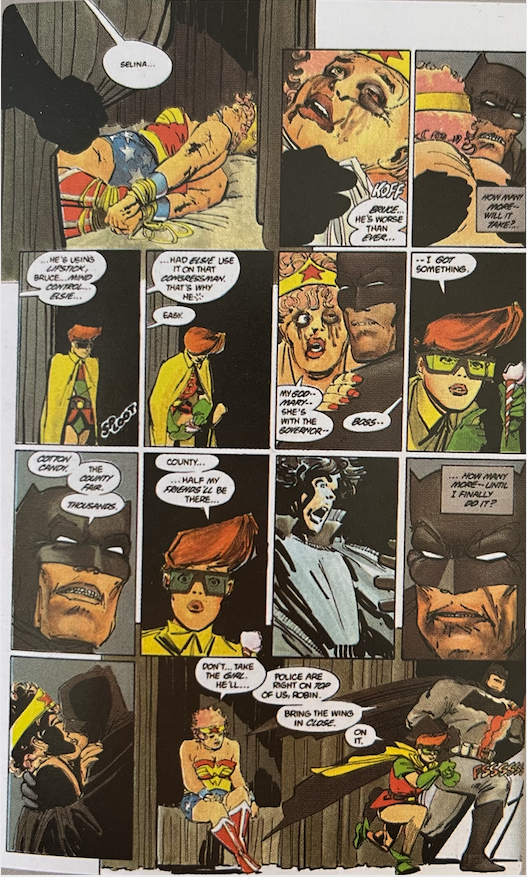

Stephen Weiner, in Faster Than a Speeding Bullet: The Rise of the Graphic Novel, speculates that the inclusion of a female Robin perhaps "captur[es] the feminist sentiment of the times."24 This new Robin is Carrie Kelly, young and bright.25 However, this female representation is arguably soured when Miller presents a beaten and tied-up Selina Kyle, a.k.a. Catwoman, wearing a "kinky Wonder Woman costume" in connection with the escort service she now runs as a retired villain.26

Batman and the new Robin rescue a beaten and restrained Selina Kyle (a.k.a. Catwoman).27

Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

"Moore's writing is remarkable. He catches the rhythms of speech so naturally, presents his world so seamlessly, that the whole seems effortless." —Neil Gaiman28

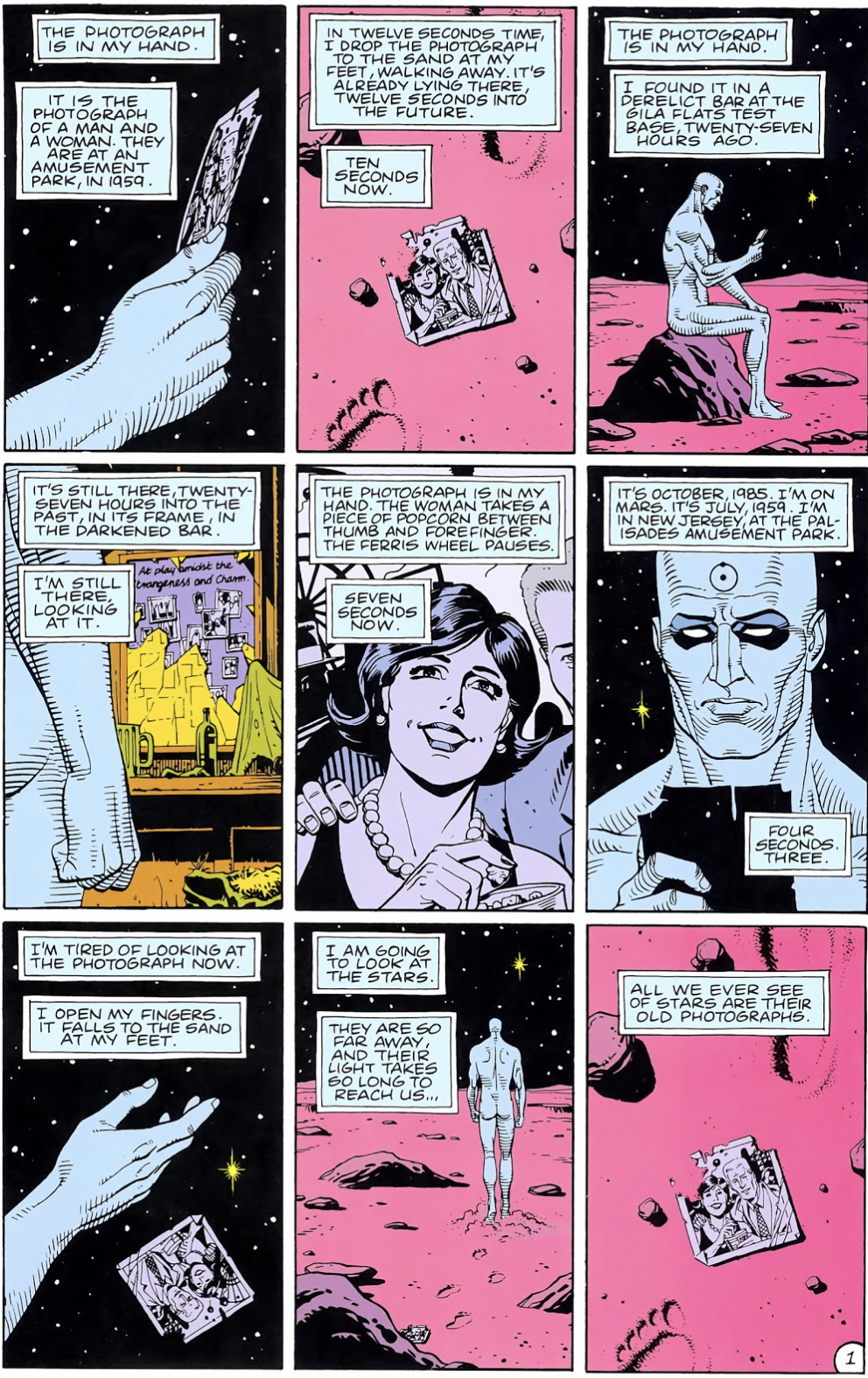

Dr. Manhatten muses over a photograph of his former self (as Jon Osterman) with Janey Slater.29

Watchmen complicated the superhero mythos in a "very complex story featuring a group of throwaway characters."30 In the world of Watchmen, President Richard Nixon was never impeached, and superheroes have been outlawed.31 Like The Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen conveys a specific message about masked heroes or vigilantes: "[D]on't get caught in a dark alley with someone choosing to wear a mask and fight crime. He wouldn't necessarily turn out to be a nice guy or anyone that you could depend on. In fact, his sanity was probably held together with masking tape."32 Packed with cultural allusions and references ("Einstein, the Bible, William Blake, Carl Jung, and Bob Dylan"), Moore and Gibbons question the "meaning of time and whether or not absolute power corrupts."33 And Gibbons's artistic skills further the story, with linear and direct artwork that captures a "literalism that belies the seriousness of the story."34

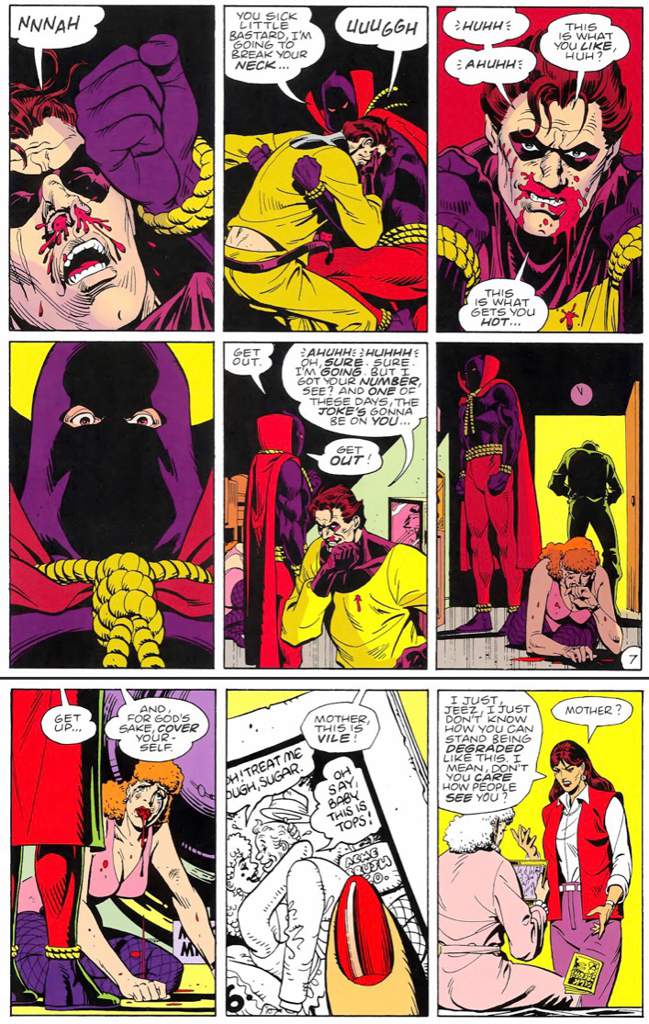

At its core, Watchmen is about "ordinary people" and the ways in which "they try to make a difference and make sense of their lives."35 However, as Lorna Piatti-Farnell explains in "'For God's Sake, Cover Yourself': Sexual Violence, Disrupted Histories, and the Gendered Politics of Patriotism in Watchmen," the story hinges, to an extent, on the sexual assault of the character Sally Jupiter (a.k.a. Silk Spectre) in the 40s—shown through flashback.36 And as the Silk Spectre, Sally wears an outfit reminiscent of 40s pin-up models, with her sexualized outfit—confirmed as sexual when Sally's daughter, Laurie (a.k.a. Silk Spectre II), expresses disgust at a pornographic comic in which her mother is portrayed in a sexual manner, while Sally looks on it fondly—reinforcing her inferior role to the men in the group.37 Laurie, too, transforms into "a sex symbol as defined by the masculine gaze," and in being continually romantically involved with other heroes, her character is of the "permanent girlfriend"—"firmly in line with comic history."38

Flashback in the narrative to the sexual assault of Sally by the Comedian.39

Maus by Art Spiegelman

"Maus is a masterpiece, and if the notion of a canon means anything, Maus is there at the heart of it. Like all great stories, it tells us more about ourselves than we could ever suspect." —Philip Pullman40

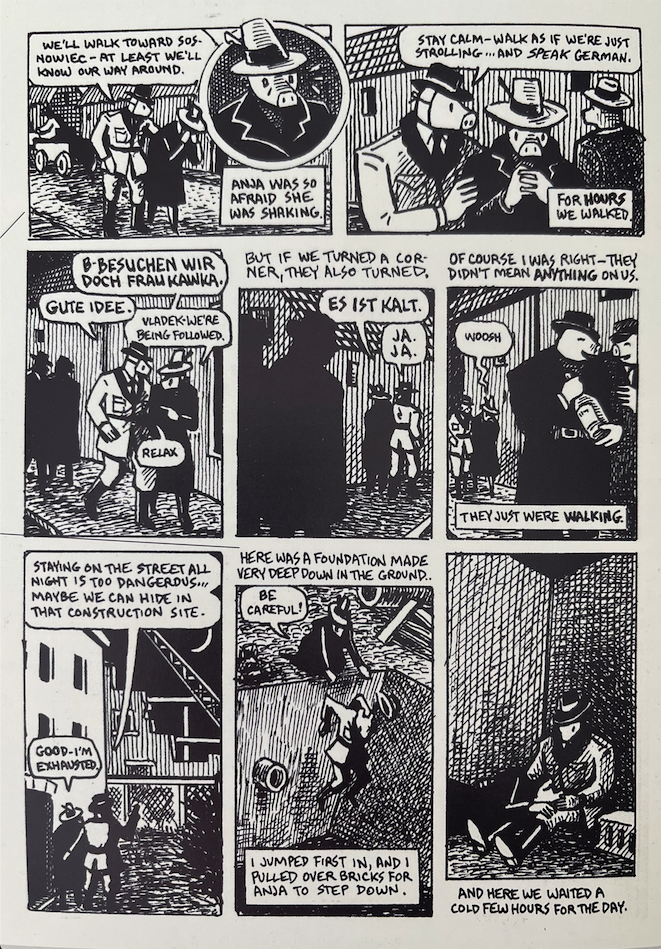

Vladek attempts to disguise himself and his wife as Poles, depicted as pigs, by wearing pig masks.41

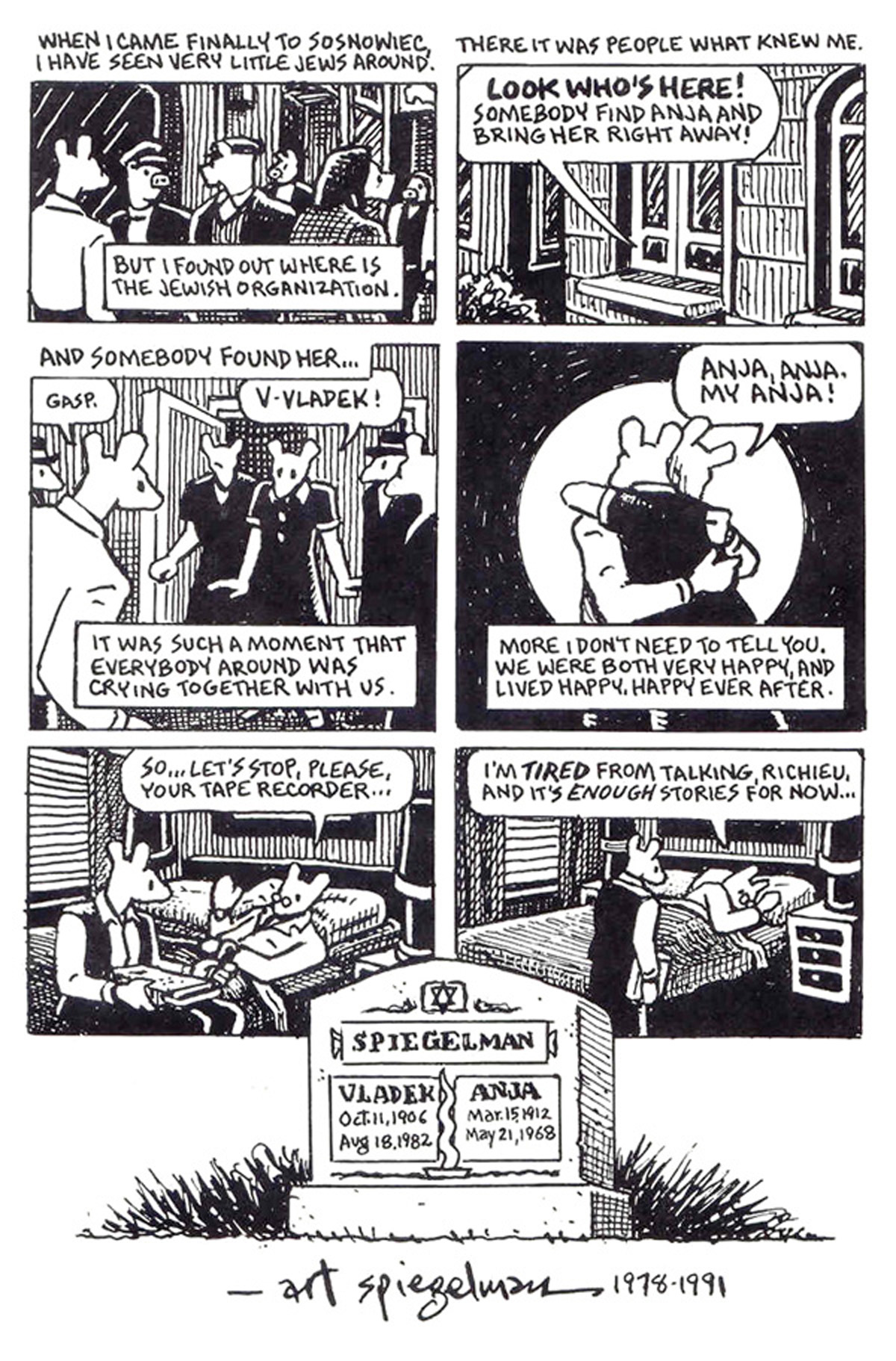

Maus tells the "intimate and unflinching history" of Spiegelman's father, Vladek, a "Polish Jew and survivor of the Auschwitz concentration camp," alongside Spiegelman's present life in New York as he "tries to rebuild his relationship with his father and … understand himself."42 (To distinguish the past from the present, Spiegelman "captures the distinct Jewish sentence order of Vladek's narrative comments, but keeps the way he and others speak in the past normal.")43 Spiegelman portrays Jews as mice and Nazis as cats, harkening to the cat-and-mouse games of early animation and comics and paralleling the "legacy of racist propaganda that used such imagery"—especially considering "Hitler compared Jews to vermin and used rat-poison Zyklon B in the death camps."44 As Stephen Weiner argues in Faster Than a Speeding Bullet: The Rise of the Graphic Novel, "the importance of Maus can not be understated," especially in terms of publication and the ensuring reception.45

A branch of Maus scholarship concerns the "muting and … general 'banishment of female voices'" in the text, particularly concerning Anja (Artie's mother and Vladek's wife), who is "silenc[ed]" with her documented suicide in the text.46 As Philip Smith argues, in "Spiegelman Studies Part 1 of 2: Maus": "The relative silence of female victims of the Shoah is a recurring and disturbing dimension of Holocaust representation." However, Philip does reference Gwyneth Bodger, who argues that the "separation of women and men on arrival at the camps often meant that men were unaware of what happened to the women, and this separation also meant that women were quite simply not a part of men's Holocaust experiences."47 But another point of contention concerning such "muzzling" relates to "Vladek's decision to burn his deceased wife's diaries," which some consider to be a "striking[] … re‐enactment of the Nazi act of burning books and people."48

In the present, Artie records Vladek's (his father) testimony, as Vladek recalls the past to when he was reunited with Anja—speaking of a happy-ever-after despite the fact that Anja would commit suicide two decades later.49

The Sandman by Neil Gaiman

"These are great stories, and we're lucky to have them. To read now, and maybe again. Then, we need what only a good story has the power to do: to take us away to worlds that never existed, in the company of people we wish we were or thank God we aren't." —Stephen King50

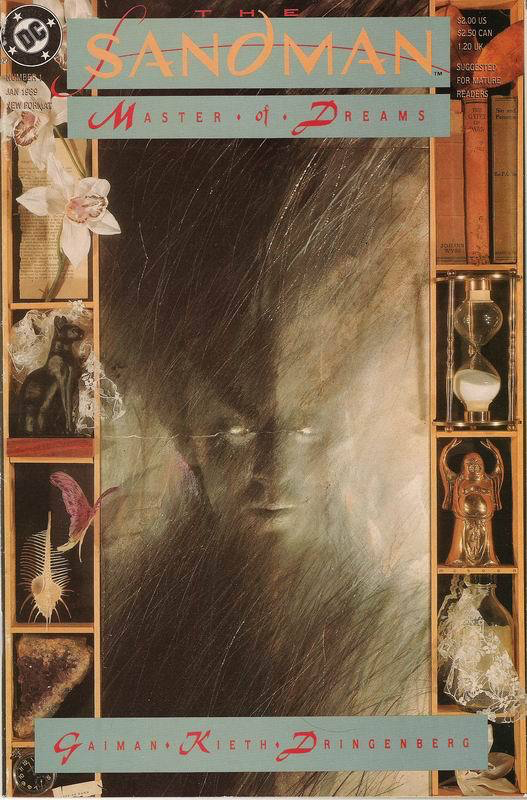

The painting and assemblage that would become the cover for The Sandman #1.51

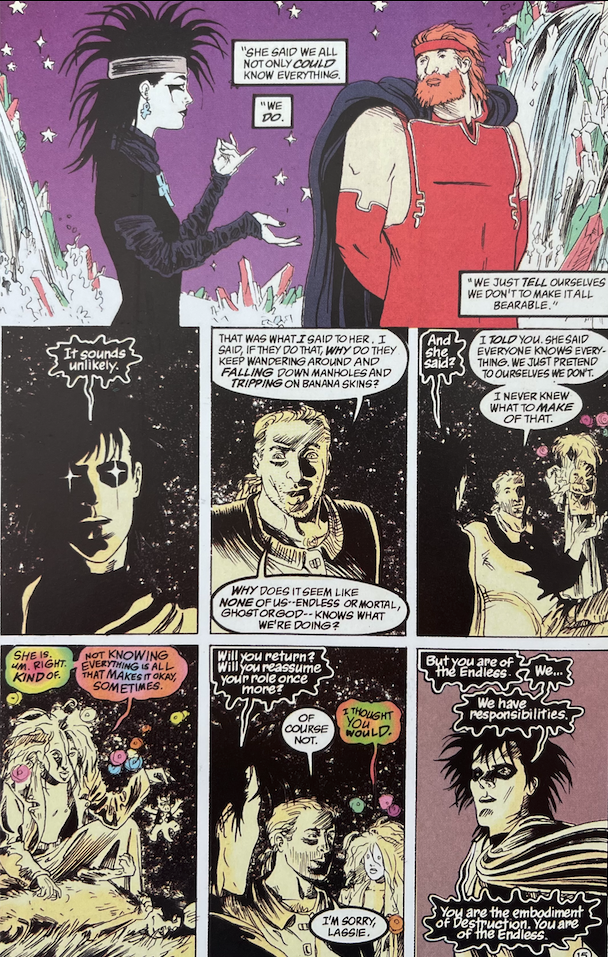

Gaiman creates a "modern mythology" in The Sandman, centred around the seven Endless, "incarnations of very primitive human states": Dream, Death, Destruction, Destiny, Desire, Delirium, and Despair.52 With strong horror-genre influences, the stories in The Sandman "veer from short, sharp shockers and tender character studies to underlying themes, steeped in literary and legendary references," of regarding the role, death, and succession of The Sandman himself, Dream (a.k.a. Morpheus).53 It was a series that "demonstrated … that a growing segment of the comic book readership had grown tired of superhero fantasy and was more interested in literary fantasy."54 And the series was certainly a hit, with it having "success with a nontraditional comic book readership" as a work that "broke with the comic book formula in many ways."55 Gaiman himself, in his personality and championing of "more literary comics," was instrumental in the success of the series, in addition to the collaborative nature of his work with various artists—as "[t]he artistic chores were given to a variety of artists, each with a different style[, and t]his constant change pleasantly surprised readers, as Gaiman wrote different storylines accenting the skills the different artists possessed."56 With a mix of "historical and mythic figures" balanced with the contemporary "supernatural and symbolic but highly personalized Endless," who "constantly bickered among themselves and ironically exhibited very human traits," The Sandman was engaging to a wide variety of readers in an "expanding comic book marketplace."57

Death responds hostilely to Dream's sulking.58

In a book review of Feminism in the Worlds of Neil Gaiman: Essays on the Comics, Sandor Klapcsik notes that a number of critics have found "feminist insights" in characters and other elements in The Sandman.59 Ally Brisbin and Paul Booth, in "The Sand/wo/man: The Unstable Worlds of Gender in Neil Gaiman's Sandman Series," delve into everything gender in the series—opening by explaining that "Gaiman renegotiates the traditional notions of gender in society and presents a practical representation of the same type of theoretical gender fluidity as developed by Judith Butler in Gender Trouble."60. Brisbin and Booth reference Mary Borsellino, who argues "that the characters in Sandman do not simply 'reinforce gender stereotypes. Rather, they do the opposite. Some of his characters are male, and some are female, but they're all people.'"61

"Gaiman, as Borsellino notes, is not trying to shock his audience with his portrayal of gender. Rather, the realism of his character development owes much to the cultural normalization of "queer." In other words, Gaiman represents queerness as a natural act simply because queerness has become more normal in contemporary society. No one adheres perfectly to gender norms, and Gaiman's portrayal of this truth is unapologetic." —Ally Brisbin and Paul Booth62

Dream and Derlirium find Destruction after he goes missing; beneath a starry sky, they discuss why he left and will not return.63

Brisbin and Booth discuss many other relevant points on gender and feminism in their article, such as how the structure of the overarching story in The Sandman "strays from the typical phallocentric style" by "'interrogating notions of story, narrative, and dream, and thus playing with the centrality of phallocentric authority'" (quoting Rodney Sharkey) in a way that is reminiscent of the work of John Fiske regarding "television texts … [as being] particularly gendered, where feminine narratives 'resist narrative closure' and masculine narratives 'are structured to produce greater narrative and ideological closure.'"64

Dream uncreates The Land.65

With "the Sandman [being DC Comics's] third-most popular character after Batman and Superman" during the mid-90s—and the series being a consistent DC best-seller, "sometimes outsell[ing X-Men]" in college towns66—The Sandman was a cult classic with "male and female readers as well as readers outside of comics."67 Tied directly to the success of The Dark Knight Returns with DC Comics as its publisher, The Sandman demonstrates a bridging of the gap between the format defining works of the mid- to late 80s with those of the new millennium, especially in terms of feminist content, wider audience focus, and inclusion of women readers. But despite being considered one of the greatest epics in the history of comics even as the series was wrapping up in the mid-90s,68 The Sandman could not entirely escape the effects of the exclusion of female readers, as Charlotte Ahlin explains in her article "How 'Sandman' Got Me Through My Teen Angst":

"[The Sandman] series is so popular with teenage girls, in fact, that female fans have become their own cliche. As [Dana Goodyear put it in her] New Yorker article ["Kid Goth"]: 'Internet critics deride Gaiman's fans as 'Twee "Bisexual" Goth Girls with BPD"—borderline personality disorder—"who are drama majors and who are destined to become cat ladies."' Because, like all media that is consumed and enjoyed by teenaged girls, Sandman must be ridiculed — God forbid young women ever genuinely like something without being mocked for it."69

This is a fitting reminder that anti-feminism remains an issue in the comics industry, and it reflects the persisting gatekeeping in the comics realm in excluding women—which, unfortunately, is still all too familiar to women comics readers today.

"'Superhero comics are the most perfectly evolved art form for preadolescent male power fantasies, and I don't see that as a bad thing. I want to reach other sorts of people, too. I'm proud that The Sandman has more of a female readership, and an older readership, than DC Comics has ever had.'" —Neil Gaiman (1992)70

Notes

1 Donaldson, "Feminism in Graphic Novels," "Introduction."

2 Madeley, "Women as Readers," "Introduction."

3 Donaldson, "Introduction."

4 Madeley, "Introduction."

5 Madeley, "Introduction."

6 Madeley, "Introduction."

7 Madeley, "Comics for Female Readers."

8 Madeley, "Comics for Female Readers."

9 Donaldson, "Second-Wave Feminism, 1970-1972."

10 Donaldson, "Second-Wave Feminism, 1973-1980."

11 Donaldson, "Second-Wave Feminism, 1973-1980."

12 Donaldson, "After 1980: The Backlash Against Feminism and Beyond."

13 Donaldson, "After 1980: The Backlash Against Feminism and Beyond."

14 Donaldson, "After 1980: The Backlash Against Feminism and Beyond."

15 Donaldson, "Impact."

16 Madeley, "Definition"; "Impact."

17 Image from Tracy Brown, David Lewis, Jevon Phillips, and Meredith Woerner, "Timeline: Downey Jr. Dances, Arnold Surprises, Spider-Man Rushes the Stage: Every Year of Comic-Con in One Giant Timeline," Los Angeles Times, July 8, 2015, retrieved April 14, 2021, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/herocomplex/la-et-hc-comic-con-san-diego-timeline-htmlstory.html.

18 Quoted in Gravett, 78.

19 Image from Abraham Riesman, "How Frank Miller Was Inspired to Build This Amazing Dark Knight Returns Page," Vulture, April 17, 2018, retrieved April 14, 2021, https://www.vulture.com/2018/04/frank-miller-talks-bernard-krigstein-dark-knight-inspiration.html.

20 Weiner, Faster Than a Speeding Bullet: The Rise of the Graphic Novel, 33.

21 Gravett, Graphic Novels: Everything You Need to Know,13.

22 Weiner, 33.

23 Weiner, 33.

24 Weiner, 33.

25 Gravett, 79.

26 Gravett, 79.

27 Image adapted from Gravett, 79.

28 Quoted in Gravett, 82.

29 Image from Cgrivas, "The greatest comic book page i've ever read (Watchmen #4)," Reddit, January 6, 2018, retrieved April 14, 2021, https://www.reddit.com/r/comicbooks/comments/7ooikq/the_greatest_comic_book_page_ive_ever_read/.

30 Weiner, 33.

31 Weiner, 33.

32 Weiner, 33-34.

33 Winer, 34.

34 Weiner, 34.

35 Gravett, 13.

36 Piatti-Farnell, " For God's Sake, Cover Yourself,'" "Abstract"; "Introduction."

37 Piatti-Farnell, "Embodying the Pin-Up, and the 'Woman as Nation."

38 Keating, "The Female Link: Citation and Continuity in Watchmen."

39 Image from deadline-cheshire, "The Problematic Portrayal of Women in Watchmen," Amino, March 16, 2019, retrieved April 14, 2021, https://aminoapps.com/c/comics/page/blog/the-problematic-portrayal-of-women-in-watchmen/aai0_ug0nBW6odE7NxxV5j8M4pEQw8.

40 Quoted in Gravett, 60.

41 Image adapted from Gravett, 60.

42 Gravett, 13.

43 Gravett, 60.

44 Gravett, 13, 60

45 Weiner, 39.

46 Smith, "Spiegelman Studies Part 1 of 2: Maus," "Anja."

47 Quoted in Smith, "Anja."

48 Smith, "Anja."

49 Image from Richard McBee, "Maus Part II, Richard McBee (blog), December 10, 2004, retrieved April 14, 2021, https://richardmcbee.com/writings/contemporary-jewish-art/item/maus-part-ii.

50 Quoted in Gravett, 98.

51 Images from Neil Gaiman, "Just to remind people of how things were done in the longago. Part of me wonders how much these would be worth today, and what Dave (aged 24) and I (aged 27) ...," Tumblr, April 4, 2021, 7:58PM, retrieved April 14, 2021, https://neil-gaiman.tumblr.com/post/647584110675722240/poisonousliasons-before-photoshop-i-miss.

52 Weiner, 39.

53 Gravett, 99, 17.

54 Weiner, 46.

55 Weiner, 42.

56 Weiner, 40.

57 Weiner, 46.

58 Image from Gallifreyan, March 10, 2017, Literature Stack Exchange, retrieved on April 14, 2021, https://literature.stackexchange.com/questions/2020/what-is-the-reason-for-partial-highlighting-in-the-sandman.

59 Klapcsik, review of Feminism in the Worlds of Neil Gaiman: Essays on the Comics.

60 Brisbin and Booth, "The Sand/wo/man," "Introduction."

61 Brisbin and Booth, "Gender and Sex in Butler and Gaiman."

62 Brisbin and Booth, "Gender and Sex in Butler and Gaiman."

63 Image adapted from Gravett, 98.

64 Brisbin and Booth, "Gender and Sex in Butler and Gaiman."

65 Image from Dave Buesing, "Sandman Universe Reading Order!," Comic Book Herald, February 27, 2019, retrieved April 14, 2021, https://www.comicbookherald.com/sandman-universe-reading-order/.

66 Erickson, "Dreamland."

67 Weiner, 46.

68 Erickson, "Dreamland."

69 Ahlin, "How 'Sandman' Got Me Through My Teen Angst."

70 Quoted in Tucker, "Cool Cult Favorites: 'Sandman'".