Timeline: A Brief History of Comics and Graphic Novels, 1930s-2000s

1930s: Comic Books

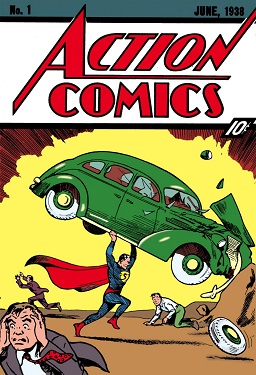

The first comic books, initially reprints of newspaper comic strips, were published in the early 30s, and the world of comic books exploded following the creation of Superman by Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster near the end of the decade.1

1940s: WWII & Teenagers

The comic books of World War II featured patriotic heroes and their sidekicks (for example, Captain America and Bucky Barnes) fighting with the Allies.3 As comic books were perceived to be a children's format, teenage sidekicks were introduced to "help children participate more fully in the stories"'—which at the time, were "predictable, often crude and enthusiastic propaganda" as many of the best comics writers and authors were fighting overseas.4 The US military supplied comic books to the armed forces, leading to many soldiers becoming "hooked on words-and-pictures storytelling" by the end of the war.5 In postwar America, the newly defined "teen-ager" group became the first generation to grow up with comic books, but by the end of the decade, interest in superhero stories had dwindled.6

1950s: New Players & the Comics Code

With a new teen audience in mind, the comic book industry focused on other genres over superhero comics, such as "funny animal stories, romance comics, and crime and horror titles."8 New players in the comic book business emerged—such as EC Comics (originally Educational Comics), whose books offered "a subversive attitude" that fascinated teens, in addition to topics such as death, violence, divorce, corruption, and the nuclear age.9 Initially satirizing the comic book industry, MAD magazine was EC's "most lasting contribution to the comics field."10 Following US Senate hearings on comic books and youth following the publication of psychiatrist Fredric Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent in 1954, the Comic Magazine Association of America formed and created the Comics Code, new regulatory guidelines wherein "women were to be properly clad, authority figures respected, and the violence toned down."11

1960s: Return of Superheroes, Comics Fandom, & Underground Comix

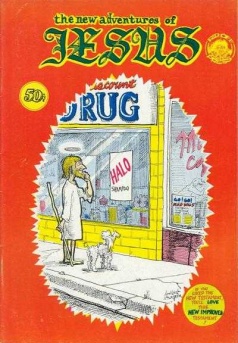

In the wake of the Comics Code, superhero stories regained relevance.13 DC Comics saw success with their superhero stories following their revival of The Flash in 1956. Stan Lee, of Marvel Comics, created a "competing band of superheroes" in response, finding success with stories of heroes facing bad guys and everyday problems, with many heroes being empowered through nuclear accidents—"offering an upside to the arms race."14 The 60s also saw the development of comics fandom through comic book conventions and fanzines, with adult comics fans recalling "superheroes fondly from their childhoods."15 But while mainstream publishers adhered to the Comics Code, the underground comix movement emerged in response—with young adults producing comic books that commonly questioned social norms, opposed the Vietnam War, focused on the sexual revolution, and told autobiographical stories.16

1970s: Comic Book Stores & Comics Code Amendment

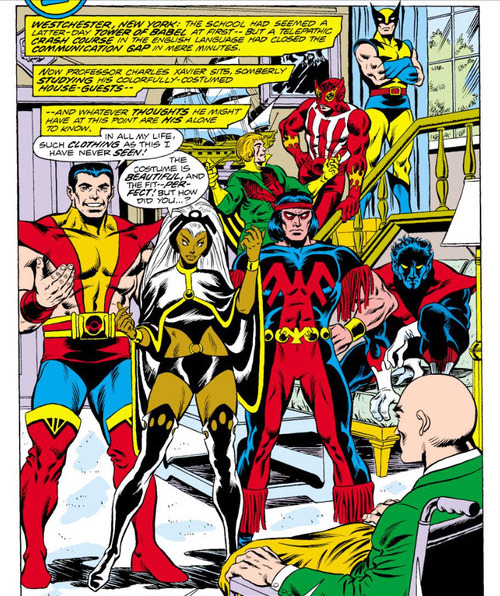

Comic book specialty stores emerged throughout the US in the early decade, growing out of preceding comic book conventions and being owned by science fiction fans and dedicated mainstream comics readers.18 However, by the late 70s, underground comix all but disappeared as they were unable to transition well into such specialty shops, in addition to being severely restricted by a 1973 Supreme Court decision that "gave local communities the power to define obscenity."19 But underground comix nevertheless impacted mainstream comics, with the movement inspiring a shift toward literary storytelling and urban realism.20 With comic book stores essentially proving that adults still read comics, publishers began to experiment with "superhero concepts aimed at older readers."21 And in 1971 after successful lobbying, the Comics Code was amended to "allow for more graphic depictions of drug abuse, organizational corruption, and the supernatural."22 For the first time, superhero comics had "African American, Native American, Asian, and Jewish characters … as leading characters rather than as sidekicks or members of supporting casts"; however, many of these characters were "overtly stereotypical and akin to characters from the blaxploitation films of the same era."23

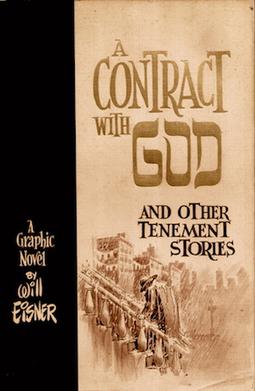

1978: A Contract with God

Will Eisner's A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories, the first modern graphic novel, was published by American trade book publisher Baronet Publishing.25 The subject matter, in addition to the presentation, of A Contract with God was fresh to comic book readers.26 Popularizing the term graphic novel, A Contract with God picked up the autobiographical style of underground comix27 to present "four thematically linked short stories that together formed a portrait of working-class Jewish life in New York during the Great Depression."28

1980s: Public Appreciation of Comics & the Developing Graphic Novel Form

Although comic book stores were still "considered suspect by mainstream culture,"30 there was nevertheless as many of 5,000 comic book specialty shops in the US at the peak of their popularity in the decade.31 The increasing usage of the term graphic novel helped to "legitimize the unique aesthetics of comics arts and facilitated the merchandising of relatively long and expensive texts," and as "readers, creators, and publishers paid more attention to long-term continuity and intricate storytelling," the general public's appreciation for comics—from "superhero comic books to avant-garde works"—was changing by the mid-80s.32 Characterized by a "furious exploration across the comics medium," the decade saw a significant and lasting development of the graphic novel format and a strengthening of the "industry commitment" to the form.33

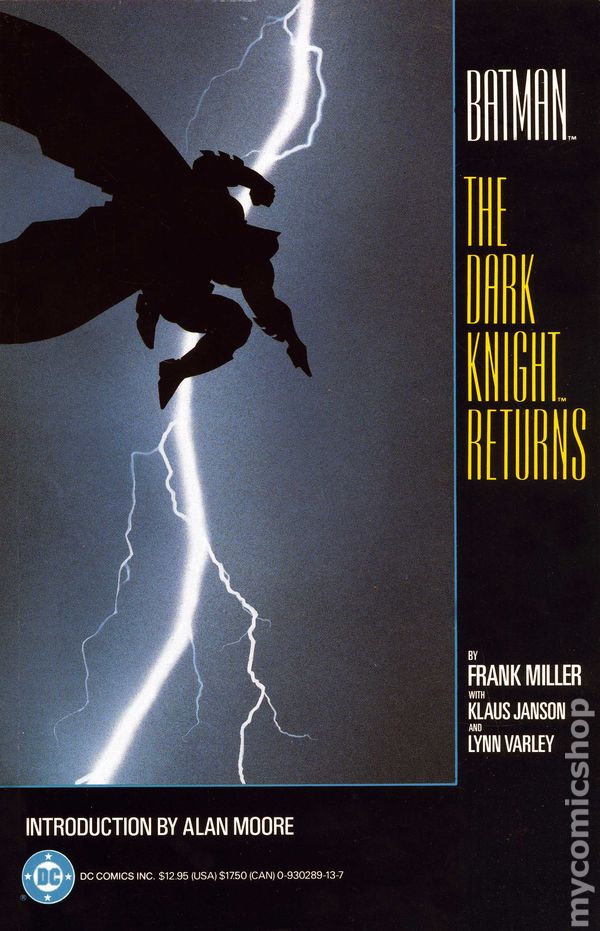

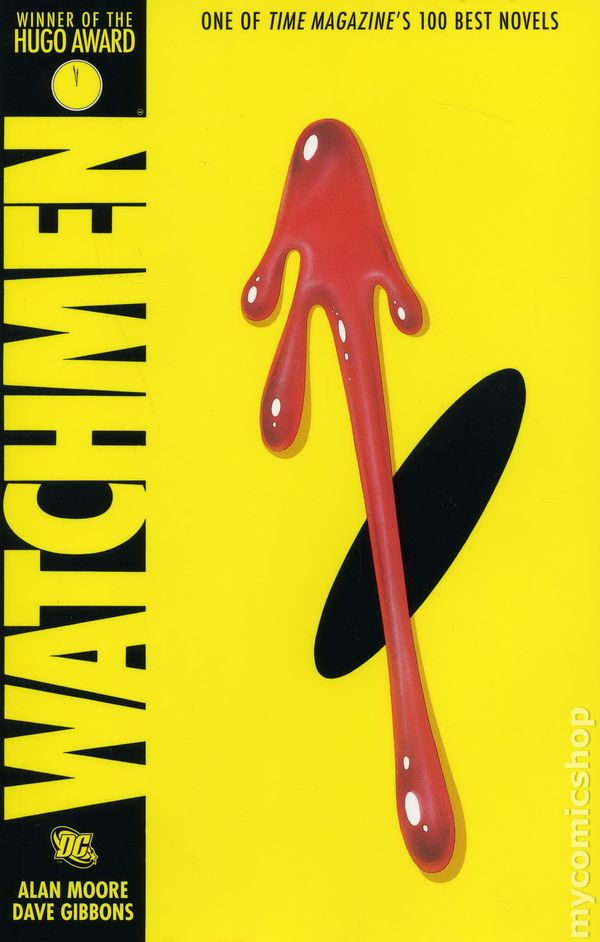

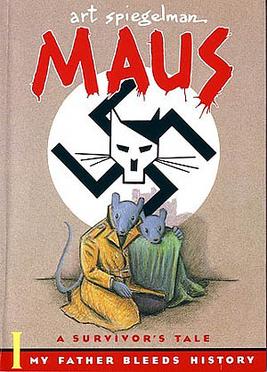

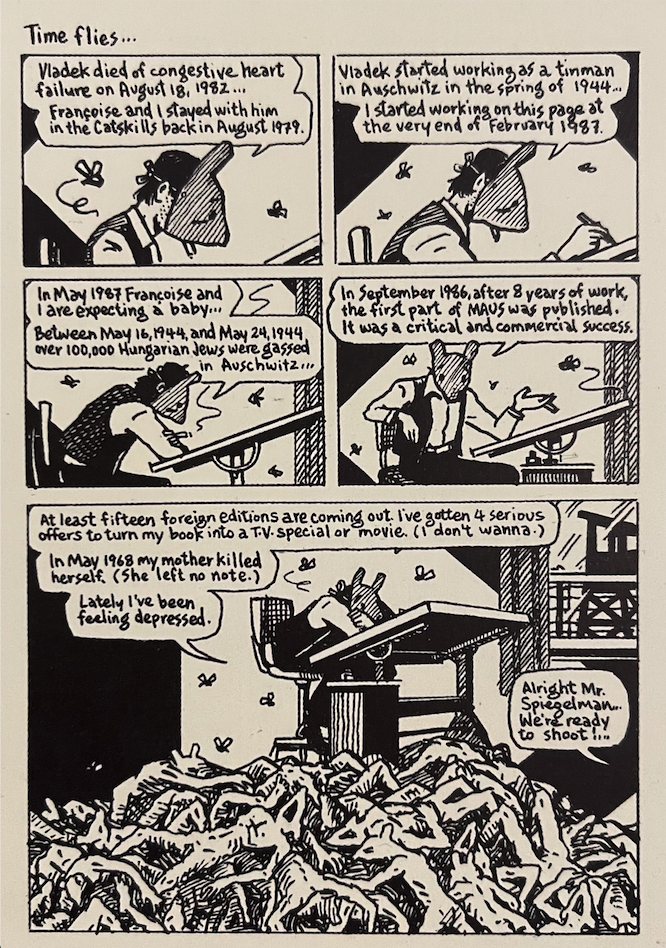

1986: The Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen, & Maus

This critical year in the history of graphic novels saw the publication of Frank Miller's Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons's Watchmen miniseries, which were collected into single-volume editions the following year35—consequently "cement[ing] graphic novels as a legitimate medium."36 Miller and Moore's "high visibility within the comics field" enabled much creative freedom and experimentation with the "hero concept."37 Miller wrote a "deeply cynical Batman story," whereas Moore put a highbrow spin on the superhero mythos.38 Another seminal work of the year was Art Spiegelman's Maus, which would forever alter the graphic novel landscape.39 Published as a book after being originally serialized from 1981 through 1986, Maus was unlike any normal comic book genre—being a "tragic, poignant, and ultimately deeply moving" masterpiece—and would come to represent a "new breakthrough into the public consciousness."40 It became loosely associated with The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen as all three were "sophisticated stories aimed at adults."41

1990s: Legitimacy & Focus on Writers

The acclaimed graphic novels of the 80s, with all of their mainstream media attention, were the catalyst for the burgeoning literary legitimacy of graphic novels in the 90s, which saw graphic novels developing into a "staple product line" for bookstore chains like Borders and Barnes & Noble.45 In 1992, Art Spiegelman won the Pulitzer Prize Prize Special Citation for Maus—a remarkable and "defining moment of legitimization for the comics medium," with Maus prompting readers to contemplate the "literary nature of the graphic novel medium as a whole."46 Prior to the decade, Marvel Comics, DC Comics, and other large publishers were not only slow to adopt the format—and rarely with original content.47 As mature graphic novels began to resonate with readers, publishers such as DC Comics began to "trust the original graphic novel format"—starting to publish titles under their Paradox Press imprint—and several other companies found success publishing graphic novels—like Dark Horse Comics and Oni Press.48 Themes and plots diversified, and the US comics world became "dominated by a stable of rising [British] writers," such as Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis.49 Small publishers focused on trusting and marketing their writers, publishing many original graphic novels, while big publishers rushed to discover the "next breakout writers and artists," sometimes signing them to exclusive, but generous, contracts.50 In either case, publishers' focus on writers would go on to lastingly shape the comic book industry.51

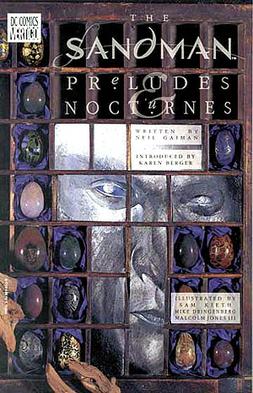

1988-1996: The Sandman

Neil Gaiman's The Sandman, was another influential and acclaimed work that represents the continuation of sophisticated and divergent graphic novel works for adult readers past the 80s. DC Comics, hoping to replicate the success of The Dark Knight Returns, commissioned Neil Gaiman to write a dark fantasy series to appeal to such readers and hook them on comics.53 Reinventing the Sandman (a 40s superhero), Gaiman created Dream, an immense being who is the lord and embodiment of dreaming—along with "other supernaturals who represented the diversity of the human condition."54 The series ran from 1988 to 1996, starting to be collected into trade paperback volumes early on in the decade.55 The Sandman, which combined elements of the horror genre with innumerable cultural references, received "consistent and growing popularity" and success, with readers and the mainstream press—capturing the attention of (and being accessible to) a variety of readers, including those new to comics.56 The Sandman received eight Eisner Awards, and the success of its graphic novel series lead to a number of supplementary books (almost all of which were not written by Gaiman), such as The Sandman Companion.57 When Gaiman left the series, DC Comics made the "unprecedented decision to end [it]."58 With Gaiman's quality themes and narratives, The Sandman was a crucial work that "pleased traditional readers and brought new readers to the comics field."59

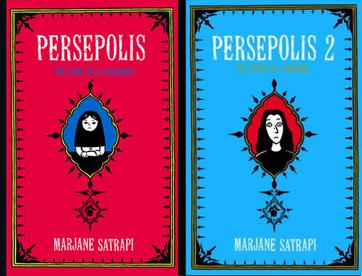

2000s: Serious and Mature Novels, Superhero Films, & Mainstream Recognition and Readership

As graphic novels became increasingly popular and accepted as legitimate literature (including being in libraries and academic spaces), the early aughts saw the publication of many serious graphic novels—particularly works that "chronicl[ed] significant historical events" and/or were graphic memoirs or biographies, such as the acclaimed and well-known Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi (published by Pantheon Books, publisher of Maus, a.k.a. the form's "most ardent supporter in the trade publishing field" during this time).61 Many works throughout the 2000s tackled serious subjects such as "war, politics, gender and sexuality, and racism, and graphic novels started being noticed by critics outside of comics-exclusive publications and awards juries outside of ones limited to graphic or comics work.62 And in a post 9/11 world, "[s]uperhero stories proved to be an effective metaphor," and the huge number of superhero films of the new millenium led to comic characters being "instantly recognizable to the world outside of comics"—with many of these films being based on the storylines of graphic novels as the format translated well to the screen.63 And other graphic novel forms gained prominence in the decade, such as Japanese manga, which exploded in popularity in the US in the mid-2000s—with manga being chiefly understood as graphic novels by American readers since serialized manga was not visible to them.64 With Persepolis having further "cemented the position of the adult autobiographical novel," as Maus had done, more and more graphic novels for adults, both nonfiction and fiction, began finding "increasingly receptive audiences" in the US, such as Clyde Fans by Canadian cartoonist Seth and Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by American cartoonist Alison Bechdel. Being supported by "institutions outside of comic book publishers," serious and mature graphic novels of the 2000s gained appreciation and respect even from mainstream readers—with graphic novels now being a solidly legitimate medium with widespread support that has taught American readers to accept and discover stories expressed in comic form.65

Notes

1 Weiner, Faster Than a Speeding Bullet, 2.

2 Image from Wikipedia, s.v. "Action Comics 1," image uploaded January 30, 2018, 00:17, retrieved April 12, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Action_Comics#1.

3 Weiner, 2-3.

4 Weiner, 2-3.

5 Weiner, 7.

6 Weiner, 3-4.

7 Image adapted from "Winter Soldier The Sidekick Who Came in from the Cold War (Part One)," Read Up on Comics - The Thought Balloon, retrieved April 12, 2021, http://www.wymann.info/comics/079-WinterSoldier.html.

8 Weiner, 5.

9 Weiner, 6.

10 Weiner, 7.

11 Weiner, 8.

12 Image from the blog post cover image to Tess Wilson, "Spider-Man Versus Censorship: A Short History of the Comics Code," Intellectual Freedom Blog, October 24, 2017, retrieved April 12, 2021, https://www.oif.ala.org/oif/?p=11376.

13 Weiner, 9.

14 Weiner, 10.

15 Weiner, 11.

16 Weiner, 12.

17 Image from Drew Bradley, "Small Press Month: A Brief History of Underground Comix," Multiversity Comics, February 3, 2015, retrieved April 12, 2021, http://www.multiversitycomics.com/news-columns/small-press-month-a-brief-history-of-underground-comix/.

18 Weiner, 13-14.

19 Weiner, 16.

20 Brokenshire, "1970's: Social Justice, Self-Discovery, and the Birth of the Graphic Novel," "Introduction."

21 Weiner, 15.

22 Brokenshire, "The Social Justice League."

23 Brokenshire, "Diverse Heroes."

24 Image adapted from Kevin O'Leary, "Giant Size X-Men Issue #1," Kevin Reviews Uncanny X-Men, September 7, 2014, retrieved April 12, 2021, https://kevinreviewsuncannyxmen.wordpress.com/2014/09/07/giant-size-x-men-issue-1/.

25 Weiner, 17, 21, 20.

26 Weiner, 20.

27 Brokenshire, "Introducing the 'Graphic Novel.'"

28 Weiner, 17.

29 Image from Wikipedia, s.v. "A Contract with God," image uploaded December 6, 2017, 22:20, retrieved April 12, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Contract_with_God.

30 Weiner, 25.

31 Weiner, 15.

32 Yezbick, "1980's: The Graphic Novel Grows Up," "Introduction."

33 Yezbick, "Impact."

34 Image from "Mystery News & Notes!," Flying Colors, January 28, 2009, retrieved April 12, 2021, https://flyingcolorscomics.blogspot.com/2009/01/mystery-news-notes.html.

35 Weiner, 33-34.

36 Yezbick, "Graphic Novels Go Mainstream."

37 Weiner, 32.

38 Weiner, 33-34.

39 Weiner, 35.

40 Weiner, 35, 38.

41 Weiner, 37.

42 Image from "Batman The Dark Knight Returns TPB (1986 DC) comic books," mycomicshop, retrieved April 14, 2021, https://www.mycomicshop.com/search?TID=525631.

43 Image from "Watchmen TPB (1987 DC) 1st Edition comic books," mycomicshop, retrieved April 14, 2021, https://www.mycomicshop.com/search?TID=514121.

44 Image from Wikipedia, s.v. "Maus," image uploaded December 26, 2017, 06:22, retrieved April 14, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maus.

45 McWilliams, "1990's: Comics as Literature," "Introduction"; "Impact."

46 McWilliams, "Comics as Literature."

47 McWilliams, "Introduction."

48 McWilliams, "New Themes and Plots."

49 McWilliams, "New Themes and Plots"; "Writers and Artists."

50 McWilliams, "Impact."

51 McWilliams, "Impact."

52 Quote from and image adapted from Gravett, Graphic Novel: Everything You Need to Know, 61.

53 Weiner, 39.

54 Weiner, 39.

55 Weiner, 41.

56 Weiner, 40-41.

57 Weiner, 41.

58 Weiner, 42.

59 Weiner, 42.

60 Image from Wikipedia, s.v. "The Sandman: Preludes & Nocturnes," image uploaded December 4, 2017, 06:58, retrieved April 14, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sandman%3A_Preludes_%26_Nocturnes.

61 Fine-Pawsey, "2000's: From Novelty to Canon," "Definition"; "Introduction." Weiner, 57.

62 Fine-Pawsey, "Significant Publications."

63 Weiner, 59, 59, 59-60.

64 Weiner, 61-62.

65 Weiner, 67.

66 Image from Wikipedia, s.v. "Persepolis (comics)," image uploaded October 7, 2017, retrieved April 14, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persepolis_(comics).